I learned from a young age how to be a hard worker. It took considerably longer to learn how to work smart.

One of the worst four-lettered insults around my house growing up, especially from my Dad, was being labeled as lazy. I don’t believe the man ever slept beyond seven-o’clock in the morning, choosing instead to spend most days bustling around and tending to this and that like a frenzied whirling dervish of perpetual motion. By today’s medical standards he qualified for a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, which manifested itself in classic symptoms of Attention Deficit Disorder. But he was from a generation that didn’t study much on such clinical terms, and dealt with his issues by simply staying busy – always busy.

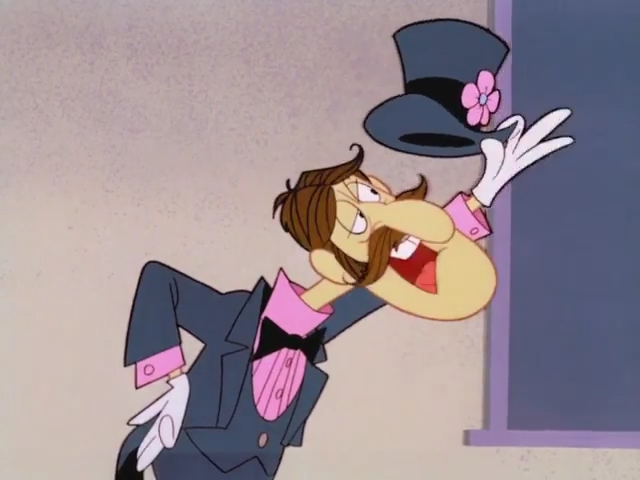

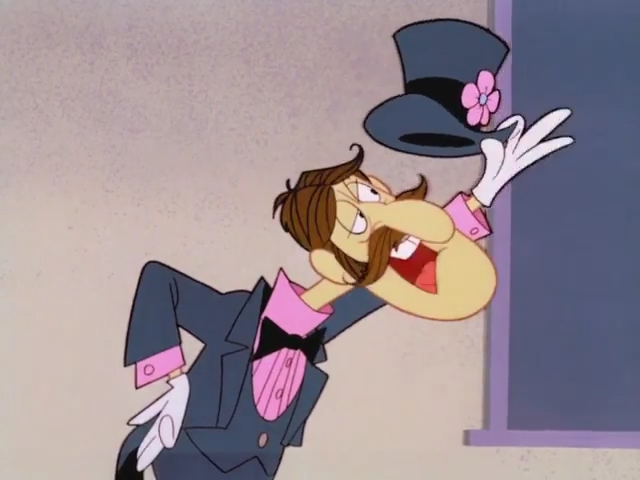

So I learned from him to wake early and buzz around doing chores at the house then working at the family business from what would now be considered a young age (I like to say that as soon as I could reach the business’s counter top, they let me run the cash register, but the truth is that I was given a stool to reach it). I would never be a lazy Farr – Professor Hinkle became my role model, endlessly chasing Frosty the Snowman around for the magic hat, and staying “busy, busy, busy”!

As I grew, however, it became harder to convince myself that there wasn’t a better, more productive way of accomplishing tasks than I was learning. Because in truth my Dad wasn’t very good at fixing things. Not that he wasn’t willing to try, but it seemed that the two primary goals he had when embarking on any project were:

-

finish the task as soon as possible

-

spend little to nothing on any repair

So the things that he did “fix” didn’t stay that way for long, and the fact that we rushed through every project lead to Machiavellian results, where often more things were dented, scratched, or broken than seemed reasonable for the intended repair.

I don’t remember my Dad ever buying a new tool (see goal #2). His workbench was a hodgepodge of ancient and strange implements, the majority of which were inherited from dead relatives or bought at the local auction house, a strange, smoky place that he attended each week. He seemed thrilled with the bargains to be found there, unlike my Mom, who wondered out loud why we needed another used coffee maker (the cord only slightly frayed), or a back-up griddle, clearly bent in the middle and smelling oddly of antifreeze and motor oil. My Dad’s answer was always that the items had been added to a pile of tools which nobody was bidding on, so Charlie, the good-natured cigar-smoking auctioneer, was encouraged to “put something with it!” in order to sweeten the deal. My Dad was a sucker for any appliance associated with breakfast food preparation, so pairing a random coffee maker or waffle iron with the box of rusty nails and set of pliers always got him into the bidding war.

I can’t be certain what the first new tool he owned was, but I know it was purchased by my Mom as a surprise gift (the surprise was that he never asked for it). In my memory, this approach to supplying him with more effective tools happened when I was in high school. By that time, I had worked with him on countless projects, and left a long trail of broken wrenches, bent saw blades, stripped and chipped screwdrivers, shattered shovels, and a variety of other outdated heirlooms and auction-fails along our path. My Dad’s initial response to these new items was to comment on “how expensive they must have been,” and to leave the things, in their boxes, under the Christmas Tree or near his beloved annual birthday cake with the peanut butter frosting.

But they didn’t stay there long. Because I opened them, amazed at this brave new world of shiny, sleek, efficient tools. I also read the instructions for some of the more complicated devices (reading instructions was another forbidden activity for my Dad – directly related to goal #1). So when the next project came around, I would show up with the new device in hand, and start using it. My Dad would either ignore the thing completely or cast a few words of scorn against it “Oh, I suppose that circular saw can cut this 2 X 4 quicker than we can by hand, huh?” Inevitably, once he got the answer to these questions he began using the tool, never actually acknowledging that studying up on the thing and bringing it to the job was a good idea, but summing that exact thought up with a statement like “Well, I guess that does work pretty well.”

The invention that finally broke down my Dad’s resistance completely was the electric screwdriver. In my humble opinion, this device is no less important in the history and advancement of D.I.Y. projects than the first Apple computers were to techies and everyone else now addicted and completely dependent on their IProducts (like my Dad, I continue to resist certain areas of “technological progress,” but I won’t rant too much here about the reasons). It’s strange for me to think that I was actually born and raised in a time when hand-held screwdrivers were the norm. For anyone who has never really considered or appreciated their cordless screwdriver, I encourage you to use only a non-electric phillip’s head screwdriver (or better yet a flat headed one) to secure a few 2 inch or longer screws into solid lumber during your next project. Although Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, like Attention-Deficit Disorder, is much more commonly diagnosed today than back in the times I’m referencing, it’s hard to believe that anyone who spent even a moderate amount of time screwing things in by hand would not suffer from it.

My Dad’s first electric screwdriver was a gift, of course, and I believe it was a Sear’s Craftsman (he considered any Craftsman tool to be top of the line, virtually indestructible, and far too expensive). I unboxed the thing, read through the directions, and charged it up, unveiling the screwdriver when we stood before a large pile of thin tin sheets which, when pieced together, were meant to become a shed in our back yard (when he showed up with a pile of metal strapped to the top of our station wagon, the rest of the family feared he had hunted it down at the latest auction, which he attended unaccompanied. But he surprised us all and announced he’d bought the kit new, from a local Agway Store which was going out of business).

Unlike other modern tools I had introduced to him, my Dad showed little resistance to the electric screwdriver, and in fact embraced the thing with such enthusiasm that you would have thought he invented it. The shed had no less than 500,000 screws which needed to be screwed in about an inch apart from each other for the thing to remain standing. These early models of screwdrivers required direct charging (removable batteries would come later), and took anywhere from 2 – 12 hours to charge completely. There was no clutch, so the screw bits often stripped (only one was supplied with the tool), and when fully charged the screwdriver was often too hot to touch. Suffice it to say that it wasn’t really designed to take on a project involving 500,000 screws, and it needed recharging multiple times with the effort. My Mom showed up halfway through the project with a second Craftsman electric screwdriver which she assured my Dad would be counted as my Birthday gift for that year (this was the start of my surprise gifts). And together with our new tools we built the shed.

For weeks and months afterwards my father would sing the praises of the Craftsman electric screwdriver to all who cared to listen. He eventually burned both of the things out, during several tasks that were far too much to ask of them, but the screwdrivers were soon replaced with Craftsman cordless drills which were better, more efficient, and undoubtedly very expensive. The most amazing part was that my Dad went out and bought them himself, and it wasn’t even his birthday. The revolution had begun.

The shed fell down under the weight of intense snowstorms several years later. I find a few of those 500,000 screws in the tall grass of the backyard to this day. Agway was long gone by then, a giant Home Depot built over it’s remains. We went there together and, like the Three Little Pigs, we replaced the ruined tin shed with a wooden one. There were more nails than screws required with the new shed, and we used a few old, rusty hammers, bending our fair share of nails along the way. I suggested purchasing a nail gun – but my Dad just wasn’t ready for something that expensive, asking me: “Oh, so a fancy nail gun could do this better than we can with hammers?” Change takes time, I suppose.

I’m not sure if there’s a straight line to my ruminations, but hopefully you’ll find something in here about the value of a strong work ethic combined with knowing how to work smart. I’m truly grateful that a solid work ethic was instilled in me from a young age. I may not have everything, but everything I have can be traced back in one form or another to hanging in there, never giving up, and working hard always. I like to think I’ve come a ways in working smart, recognizing that the right tool and the proper equipment do make a significant difference in the quality and longevity of almost every project. Hopefully my own kids, the grandkids that my dad never got to meet, will recognize that although I’m the one always up by seven-o’clock and blustering around in my own self-created frenzy most of the time, that working hard and working smart are skills and character traits that are worth passing down through the generations…

Wow, you brought back so many memories. He also was devoted to the electric knife. (I hated it). Everyone got one for Christmas one year. Since paintings and papering would lead to huge fights I took that project on alone in later years. Always a summer project. Two unforgivable traits in the Farr family were no laziness and selfishness. During household also. I still have to earn my cup of tea in the morning. Have to make my bed or start a wash. As you say old habits die hard. I have learned to work smarter, or hire people. Getting older helps. Our values are admirable, but moderation helps. He certainty was a character. I can still see him shaking his head, and saying, Well, look at that! when something he fought turned out to make life easier. What a guy!